Brexit, Britain’s decision to leave the European Union, has plunged the country and a good proportion of European OTT services into a three-year-long crisis that is not over yet.

On 16th October, with the latest Halloween Brexit deadline looming large, Sky News launched a new pop-up channel, ‘Sky News Brexit-Free’ offering a primetime news source without any of the Brexit content that was dominating the mainstream agenda.

“A study released this summer found that a third of people are avoiding the news entirely,” the broadcaster said in a statement. “More than 70% of them blamed Brexit, saying they were too frustrated over the political debate surrounding it.”

In the end, events overtook the channel (very briefly the government failed in its attempt to get the bill through parliament, a general election was held on 12 December which returned a Brexit-backing Tory majority, and the latest Brexit deadline has been pushed back to 31 January 2020).

But the broadcast industry will probably sympathise with the frustration evident in the survey. Political viewpoints aside — and in the language of Brexit, the media industry is a staunch ‘Remainer’ with 67% saying they wanted to stay within the EU before the referendum was held — the tumult and uncertainty caused by the ongoing process have at the very least been bad for business.

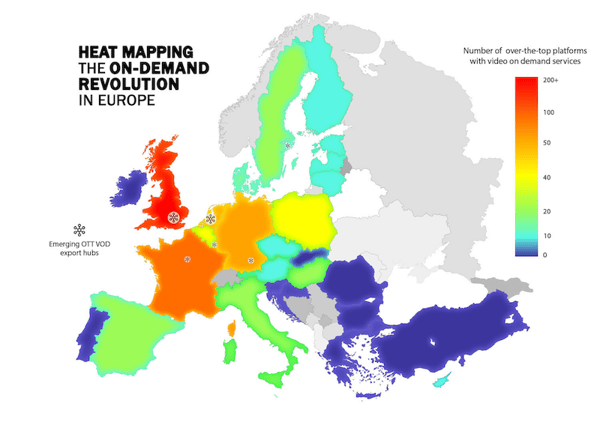

And given the UK’s prominent role in European OTT, in particular, that’s having lots of ramifications. In 2017 the UK was classed as the leading European OTT hub, with 82 of its 226 OTT services targeted abroad, twice the number of any other nation. The picture two years on is very different.

Brexit: How we got here

To recap briefly, a referendum was held over whether the UK should leave the European Union on 23 June 2016, and in a surprise, the result returned a ‘Yes’ vote by a 52:48 margin. This was then enshrined in legislation and the word Brexit (a portmanteau of the words ‘Britain’ and ‘exit’) began its journey to dominating political discourse in the country. That it hasn’t happened in the three and a half years (and counting) since is a mark of how complex the task of unravelling forty-plus years of interconnected laws, legislation, and agreements is — the UK joined the EU in 1973 —, especially when the country is so evenly split.

(For anyone who wants to read more about the wider situation, The New York Times has a decent, succinct, and fairly even-handed explainer of the ins and outs of the process and some of the issues bedevilling it here.)

For the broadcast industry, the effects of the ongoing uncertainty have been extremely difficult to handle. On the one hand, you have the wider problems that all industries are facing, such as the poor exchange rates that have taken hold since the referendum and the prospect of a potential skills shortage. 47% of the workforce in the UK’s VFX and digital animation industries, for example, are from overseas, and there is still a distinct lack of clarity over the ongoing status of the 33% of workers in the sector from mainland Europe once the free movement of labour is ended and future governments get to introduce their own new immigration and working visa policies.

And any planning organisations might attempt to do for all this is complicated further by the fact of having to account for a ‘no-deal’ scenario. There are two main possible outcomes to the whole Brexit process: a managed deal struck between the UK and the EU which sets out a framework for trade negotiations to take place and a ‘no-deal’ scenario where Britain crashes out of the EU with nothing. Given the level of brinksmanship at play both in the UK and the EU, that latter has already come within a few days of happening several times. The result is that companies have to plan for two different futures with may or may not happen at extremely short notice. A third scenario, where the UK presses the reset button and the whole thing is forgotten about, is technically feasible but looking increasingly less politically likely.

Introducing the Audiovisual Media Services Directive

The key bit of legislation that is reshaping the European OTT landscape is the Audiovisual Media Services Directive (AVMSD) and working out what replaces it in the UK in any post-Brexit world.

The AVMSD sets out what is known as the country of origin principle, which effectively means that television broadcasters and video-on-demand providers can transmit services across the EU, provided they comply with the rules of the country which has jurisdiction over the service. Establishing that jurisdiction, the country of origin is a fairly involved process with multiple different criteria such as where the head office is registered, where editorial decisions are made, where staff are located, etc.

But the key takeaway is this: once the AVMSD no longer applies to the UK, any UK licensed broadcasters will no longer be guaranteed the freedom of retransmission in other EU member states. Indeed, if they want to continue to broadcast into Europe under the AMVSD they may need to restructure their European business and obtain a new broadcast license in another European country, following which they will then need to submit to its legislative authority.

Given the potential for a no-deal Brexit to occur rapidly and without any transition period, several broadcasters have already voted with their feet and moved their operations. To date, and this is by no means an exhaustive list, Turner Broadcasting Systems, NBC Universal, DAZN, and Discovery have moved their operations out of the UK and secured German broadcast licences, while Discovery has also moved its European HQ for its pay-TV portfolio to the Netherlands.

AETN’s application for a license from the Bavarian broadcast authority BLM highlights the international nature of the flight from the UK. It ran 14 thematic channels licensed by Ofcom in the UK targeting audiences in the Netherlands, Poland, Sweden, Romania, Belgium and more. These will now be run out of Germany.

Even the UK’s preeminent public service national broadcaster, the BBC, has moved several of its broadcasting licenses to the Netherlands so it can continue transmission of some of its European commercial channels in the wake of a no-deal Brexit.

And there are a few other issues worth mentioning here too, mainly that will impact consumers as a result of leaving the Digital Single Market. UK citizens will no longer be able to have content portability of their paid online services when abroad (and vice versa for EU citizens travelling to the UK). These could be renegotiated by the individual service providers but this is a complex process and considered unlikely.

There will also likely be a return to roaming surcharges for mobile network access while travelling in both directions. Pan-European groupings of the largest service providers will be able to mitigate against this to a degree, but the guarantees that took so long to put in place about this will be null and void.

So where are we (and European OTT services) going?

As well as the previously mentioned European OTT services figures, in 2017 12% of all channels broadcast in the EU were based in the UK. Every EU country had channels — ranging from six to 77 – that were licensed by Ofcom, the UK regulator, and broadcast in their local market.

Source: TVT Media

The research has not been repeated in the past two years, but those numbers will undoubtedly be substantially lower and we are seeing a reshaping of the European market as a result, with the Netherlands and Germany in particular both becoming important broadcast hubs. For the UK, this pivot has been difficult to say the least; research from media analysis firm Oliver & Ohlbaum for the Commercial Broadcasters Association (COBA) highlighted the fact that international networks invested £1.02 billion in the UK in 2017, a 50% increase over six years. COBA also claims one in five TV jobs in the UK are related to international channels. These jobs and that money can probably be put in the ‘at risk’ category.

Also potentially at risk is the UK’s pioneering role in addressable advertising. The UK has a massive advertising industry generating £24bn and employing 350,000 people once you add it all up, and it has been aggressively pursuing the addressable opportunity. Sky’s AdSmart alone reaches over 30 million viewers in the UK and Ireland, around 43% of the total population, and the country’s biggest commercial broadcaster, ITV, is to launch its own platform in early 2020.

The problem is data. Beyond the fact that its own internal solutions consider the UK and Ireland to be a single market — and the 500km long border in Ireland is one of the defining problems of Brexit — ad solutions are increasingly looking to scale internationally. If the UK leaves the EU under a no-deal Brexit it automatically becomes classified as a third country and data flow becomes compromised. As The Drum details, firms will need to abide by the GDPR and the UK’s own Data Protection Act 2018.

“The EU uses a legal mechanism called data adequacy to allow the transfer of personal data from the EEA to a third country,” it explains. “The UK government has announced that it will allow the flow of personal data to the EEA regardless of a deal being in place and will recognise existing European Commission data adequacy decisions. However, the EU has not yet made a similar commitment to the UK. Hence, if we leave the EU without a deal, it is highly unlikely that we will have a data adequacy decision in place.”

In other words, data can flow unrestricted to the EEA but not the other way around. Industry body the Advertising Association basically recommends mapping data flows and seeking legal advice. What the implications of all this will be are, as yet, unclear.

And, three and a half years after the whole process began, there are still plenty more unknowns too. On the subject of replacing the AVMSD post-Brexit, the UK government’s favoured mechanism currently seems to be to revert back to the previous European Convention on Transfrontier Television (ECTT) ratified in 1993. However, this does not apply to VOD (VOD services not under UK jurisdiction that are currently available to UK audiences will continue to be available, says Ofcom — which is good news for Netflix based in The Netherlands). But furthermore, as the UK industry association the DTG puts it:

“The ECTT sets out that EU countries should apply the AVMSD not ECTT between each other. This means that even the EU countries who have signed ECTT observe only AVMSD rules inside the single market.”

This, of course, means that it is of no real relevance in 2019, which contradicts the government’s earlier advice. Indeed, Broadcasting and video-on-demand if there’s no Brexit deal (published September 2018) and Broadcasting and video-on-demand, if there’s no Brexit deal (published October 2019), have several differences between them, of which the ECTT information is only part of it.

In the midst of all this uncertainty, the UK could still crash out of the European Union on 31 January, a little over two months from now. And if you are reading this long after that date has receded, the chances are that uncertainty will still be the order of the day too. There’s a joke doing the rounds in the UK that goes something like “The year is 2385, and the British Prime Minister appears before the European Parliament once more to ask for an extension of the Brexit deadline. No one knows when this ancient ceremony first started or, indeed, what Brexit is.”

Sadly, the broadcast industry in the UK is only too aware of what it is and what its implications are: one of which will be to dramatically minimise the importance of the country as a hub for European OTT and other broadcast operations And, with so much still up in the air and subject to political whim, it may not be over yet…