A whole new era of personalisation is promised by object-based media. Here’s a quick introduction to the technology and where we are with it.

2019 has already been an important year when it comes to new ways of telling stories via television. Black Mirror: Bandersnatch, released by Netflix at the end of 2018, showed a glimpse of the future with its branching, viewer-selectable storylines. We covered it in detail, analysing the technology behind it and the potential market for such entertainments, here. Since then Netflix has said it is doubling down on interactive storytelling.

2019 has already been an important year when it comes to new ways of telling stories via television. Black Mirror: Bandersnatch, released by Netflix at the end of 2018, showed a glimpse of the future with its branching, viewer-selectable storylines. We covered it in detail, analysing the technology behind it and the potential market for such entertainments, here. Since then Netflix has said it is doubling down on interactive storytelling.

“It’s a huge hit here in India, it’s a huge hit around the world, and we realized, wow, interactive storytelling is something we want to bet more on,” Netflix VP of product, Todd Yellin, said at a conference in Mumbai. “We’re doubling down on that. So expect over the next year or two to see more interactive storytelling.”

First out of the gate is going to be an interactive special — and final ever episode — of Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, which (at time of publication) is currently in post production, and there are definitely more titles in the pipeline too. Arguably though the most interesting interactive title released this year was the 1000th episode of the BBC’s technology magazine programme, Click, as this was assembled from a kit of object-based media components.

Unlike the interactive branching used in Black Mirror: Bandersnatch, object-based broadcasting allows the content of programmes to change according to the requirements of each individual audience member. And it not only enables interactivity, it enables a whole new degree of potential personalisation for TV programmes of all genres.

What is Object-based Media?

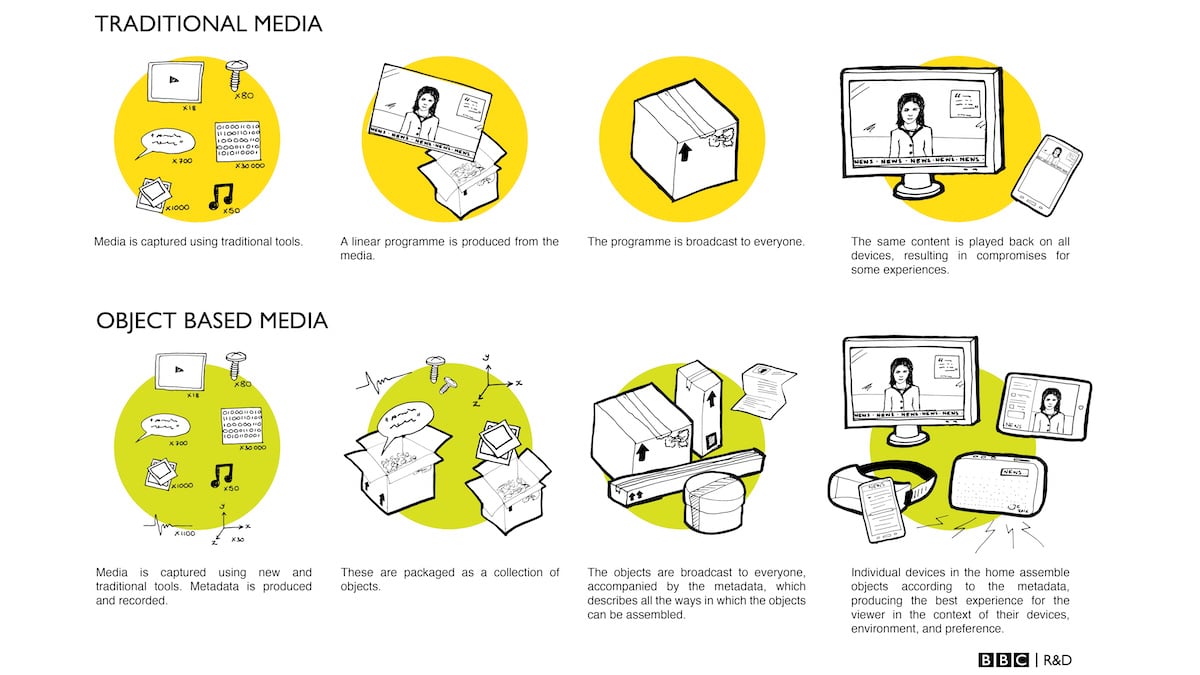

At its heart, the concept of object-based media is almost disarmingly simple; the objects in question are all the different assets that combine together to make a piece of content. They can be large objects such as the audio or the video for a single scene, or they can be small objects such as an individual frame of video or a single sound effect.

They key is that by breaking them down into separate objects, they can be put back together again in different ways. Obviously to make any sense there have to be certain rules involved, so the objects also have meaning attached to them via metadata and the way they are rearranged also needs to be constrained to certain parameters.

Most of the pioneering work in the field has been undertaken by the BBC, and it explains it all in this neat graphic.

You can almost think of it as Just in Time production for content. Programmes are assembled on the fly on object-based media platforms and then the individual devices in the home or elsewhere assemble those components into highly individualised viewing experiences.

The corporation provides a range of object-based media examples that it says will reflect a day in the lives of BBC audiences in 2022 (the timeframe seems slightly ambitious but we’ll let them run with it) which illustrate well a range of object-based media use cases.

- Hyper local weather forecasts synced with the users near-future calendar. Deaf viewer given signer by default

- Soap opera catch up show set to a user-definable length

- Sports coverage with a bias towards the viewers’ supported teams

- Different audio mixes for different viewers with automatic detection of who is in the room

- Podcasts that exactly match the length of a commute/gym session

- Coverage of large events such as Glastonbury tailored to individual music tastes, even with the option of certain instruments deleted to allow playing along

Plus of course it gives plenty of examples from the production standpoint too, especially how this could potentially save a huge amount of time when it comes to reversioning content for different audiences.

Squeezebox is an example, a tool for re-editing news stories to different lengths. Footage that’s uploaded to Squeezebox is automatically analysed and segmented into individual shots. Then, rather than manually editing the footage to create different shots, an editor marks up the most relevant and important portions of each shot, indicating that the rest is a candidate for being cut (as always with many modern broadcast workflows, the quality of this initial metadata carries through the system). The editor also marks up the priority of each shot, determining how the footage behaves as the duration is reduced - which shots will hit the cutting room floor first, and which ones will be preserved.

Using this metadata, Squeezebox enables editors to adjust the duration of the story using a simple slider control. A purpose-built algorithm establishes new in and out points per shot, and in some cases drops shots entirely.

Scaling Object-based Media

An impressive amount of the BBC’s R&D work on object-based media to date has been in creating the tools for it to scale, as well as defining its components and the way they interact. As detailed in the paper Moving Object-Based Media Production From One-Off Examples To Scalable Workflows presented at IBC2017, this is a complicated process. Take the data structure alone. At the top level there is a Story, which holds a collection of Narrative Objects. Narrative flow possibilities are expressed using one or more Links to other Narrative Objects. Each Link has an associated Condition, a Boolean expression composed of any state available to the OBM experience - variables holding information such as time of day, locale, and the viewer’s choices, preferences or profile. These links are evaluated in sequence until a Condition returns true, thus establishing which Narrative Object will be visited next.

As any even light reading around the subject of interactivity will alert you, this form of content in its current state is complex, time-consuming and expensive to produce. It is also, as yet, not perhaps as sophisticated as it could be. You can experience the Click 1000 episode following this link (it only works on Chrome or Firefox) and it certainly feels like following ‘traditional’ branching content, as if the objects here are all rather large ones and tend to be 30 second chunks of video. But that said the way that it lets you delve deeper into some subjects and skip past others is interesting. And there is a very arresting and pertinent point towards the end where the presenter turns to you and says ‘Based on the choices you’ve made so far advertisers would categorise you as a…”

An Object-based Future?

It is, of course, early days with the technology; there are no object-based media standards as yet and it is undeniable that some of the programmes being made with it scream gimmick. But there is a lot of promise there and some of the less complex use cases, such as personalised weather forecasts, may not be too far in the future. It’s also well worth remembering that there is a whole important layer of user personalisation that object-based media enables before you start getting to high-level interactivity. As SMPTE points out, that covers such basics for the viewer as enhanced on-screen graphics for people with poor vision to the automatic inclusion of sign language presenters.

PwC’s latest Global Entertainment & Media Outlook 2019–2023 Report highlights the importance of personalisation to the industry, titling it ‘Getting personal: Putting the me in entertainment and media’.

“Increasingly, the prevailing trend of consumption, especially in markets where broadband penetration is high, is for people to construct their own media menus and to consume media at their own pace,” it says, exhorting companies to know their consumers, focus on user experience, and “remember the individual behind every user ID.”

Developments in technologies such as object-based media fit into that future very well. The BBC’s imaginary schedule for 2022 seems a long way off still technically, but in the current industry, a lot can happen in three years.