One of the key trends in mature OTT markets is the ability to offer ‘rival’ content as aggregation in OTT becomes not just mainstream but expected.

While the importance of offering content is widely understood in the current TV marketplace, the ways that different operators choose to follow that path are varied. Content is expensive to produce — and, indeed, in the current coronavirus outbreak impossible to do so — so the path of buying it in and aggregating it in your own service has always been a popular one.

While the importance of offering content is widely understood in the current TV marketplace, the ways that different operators choose to follow that path are varied. Content is expensive to produce — and, indeed, in the current coronavirus outbreak impossible to do so — so the path of buying it in and aggregating it in your own service has always been a popular one.

In many ways it has always been thus. One of the defining aspects of the Pay TV era was the rise of the carriage deal and the ability of platforms to carry other services than their own. This is a long-established business practice, but can still occasionally blow up in people’s faces in a fairly public manner. For instance, last year Viacom began running crawls and promo spots on its channels warning viewers that its Nickelodeon, Comedy Central, BET, MTV and other channels would soon go dark on AT&T’s DirecTV when the current contract expired (as usual, a deal was signed at the last minute).

The rise of OTT has, of course, changed the landscape completely here as it has elsewhere. And the result, as the competitive landscape has become more fractured and tortured in recent years, has been some very surprising bedfellows.

Competing for HDMI 1

We’ve written about this several times in the past years. In Apple TV, Sky Q, and the Ongoing Battle for the HDMI 1 Slot we characterised the movement from aggregator to super-aggregator as being the battle for the HDMI 1 slot. Aggregators provide content services from several sources; super-aggregators have the ambition of being the sole intermediary for all content, whether that be linear or non-linear content, pay and free to view content, or premium and UGC content. The ambition is to be the ‘gatekeeper’ and owner of the one device that is plugged into the converted HDMI 1 slot that is the first accessed by television sets as they boot up.

That gives them a powerful position. That means the new app-based TV landscape is under their control with, for example, a Netflix app sitting prominently on the home screen but under an automatic playout of whatever content the super-aggregator is promoting at the time or is being surfaced by content recommendation engines.

As can be guessed, it’s not a cheap position to vie for. It confers responsibilities of platform distribution and maintenance, the execution of important features such as global search, and more. It needs a powerful device to make it work — or a fully-featured cloud-based service as is becoming more typical — but equally, it is a powerful one.

It is also a response to changing consumer behaviour. While service stacking has been part of the OTT landscape for a while now, the proliferation of services we have seen in recent months (with more high-profile ones to come) is testing the resolve of even the most dedicated consumers. According to a recent Global Web Index survey, subscription fatigue is becoming a real issue.

36% of consumers cite their biggest frustration as being the sheer cost of managing multiple services; 28% expressed frustration at having to maintain multiple services; meanwhile 47% said they would pay for another sub if there was something they were interested in; and only 10% said they would cancel one subscription before starting a new one.

These slightly mixed messages hint at tension in the market between desire and practicality. More data from Global Web Index goes on to say that 3 in 4 consumers feel they have just the right amount of subscriptions while close to 1 in 5 say they have too many.

Of course, the proliferation of subscriptions has been mirrored by a period of dis-aggregation, for want of a better term, amidst the OTT suppliers, probably the best-known example of which was Disney pulling its Marvel titles from Netflix. It was moves like this that led to a widespread belief that we were moving towards the end of the Golden Age of Streaming and the replacing of the era of cheap, easily available content with increasingly vertical and siloed premium services.

An aggregator of apps

If anything though it looks like we are moving into a new period of aggregation. While operators can’t realistically do anything about the mushrooming cost of signing up to multiple services, some of the super-aggregators in the market are at least making moves to roll all these payments into one. Being able to pay for your Netflix service through your Pay TV provider (and, of course, access it via their STB) is becoming an increasingly common option.

And we are starting to see some impressive moves at the top end of the market. In France, Canal+ has negotiated an exclusive deal to distribute Disney+ on its Pay TV service, and Vivendi CEO, Arnaud de Puyfontaine, has said that the business is “evolving from an aggregator of content to an aggregator of apps” and is working towards becoming “the best gateway to the content most desired by French customers.” Meanwhile, in the UK BT has launched an entire new slate of aggregated TV packages. As Rapid TV News puts it: “Specifically, this will mean that the BT TV customers can watch from the one source Sky Atlantic original programming; box sets; films; live sporting action on Sky Sports from NOW TV and BT Sport in 4K; Amazon Prime Video; and Netflix in 4K.”

Sky Atlantic has long been one of the jewels in the Sky crown, populated as it is by content from the long-standing deal the broadcaster has done with HBO, and has been jealously guarded. Of course, under existing deals Sky can also offer BT Sport to its customers, indicating that the differentiation between the two services will soon have to come down to something other than content.

Maintaining advantage

All of this raises an interesting question: when everybody offers largely the same content, what it is that gives services a competitive advantage?

Arguably it is the way that service is delivered. The User Experience is vital here. We wrote about this last year (see Why UX Design Comes Before UI for TV), but the tl;dr summary comes near the end.

- Be useful - meet expectations and add value to the service

- Be usable - maintain ease of use

- Be findable - can the consumer find what they want quickly?

- Be credible - provide what the consumer genuinely needs

- Be desirable - do consumers want to use it?

- Be accessible - work across languages, generations, abilities and more

- Be valuable - provide real results

It is a challenge and there is no doubting the important technology choices that have to underpin it. But for operators increasingly moving towards offering app aggregation, there is still a distinct competitive advantage to be had in offering an excellent service at an attractive price point.

It does also open up the gaps too. While price sensitivity is always going to be front and centre with some consumers, a reduction in the number of individual services a consumer is signed up to (even if they are paying the same price, just to one super-aggregator) psychologically opens up the prospect of adding more.

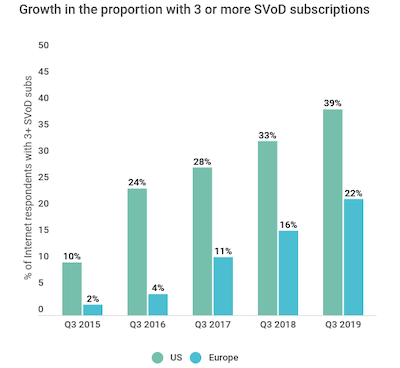

And according to Ampere Analysis in the graph below, the proportion of Internet users with three or more SVOD subscriptions in the US grew from 33% to 39% from Q3 2018 to Q3 2019, while the European figures rose from 16% to 22%.

The trend is upwards and, with super-aggregators an increasingly common presence in many markets, there may soon be more space for more content in the ‘gaps’ in the market they create.